Science for AI

Looking back at the development of artificial intelligence in recent years, Diffusion Models and Transformers stand out as two undisputed milestones. Notably, the core intuitions behind both technologies originated outside the field of AI: Diffusion Models draw from research on particle diffusion and reverse diffusion in non-equilibrium statistical physics, while the attention mechanism—the foundation of the Transformer—corresponds directly to the process of selective attention in human cognitive psychology.

Looking back at the development of artificial intelligence in recent years, Diffusion Models and Transformers stand out as two undisputed milestones. Notably, the core intuitions behind both technologies originated outside the field of AI: Diffusion Models draw from research on particle diffusion and reverse diffusion in non-equilibrium statistical physics, while the attention mechanism—the foundation of the Transformer—corresponds directly to the process of selective attention in human cognitive psychology.

If we examine history further, we find that this kind of “external inspiration” is not an isolated phenomenon. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) introduced game theory into the generation process, constructing an adversarial system between a generator and a discriminator; the effectiveness of Residual Networks (ResNet) can be mathematically viewed as the result of discretized Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs). Based on these observations, I believe it is necessary to propose a new perspective distinct from the current status quo: Science for AI.

Currently, the academic community is more enthusiastic about discussing “AI for Science.” Whether it is AlphaFold’s breakthrough in protein structure prediction or AI Feynman’s application in discovering physical equations, the paradigm of these celebrated works is generally consistent: treating machine learning as a high-dimensional statistical tool to process data from scientific domains. I do not deny the value of this tool-based perspective, but it has limitations: it primarily utilizes AI’s capacity for fitting, yet often overlooks the structural insights accumulated by scientific disciplines over centuries, as well as the abundance of elegant properties inherent in these fields.

Science for AI advocates an inverse path: leveraging mathematical structures with proven, favorable properties from the natural sciences to investigate the nature of intelligence.

Let us look at a few specific cases that demonstrate how intuitions from natural science are projected onto intelligence.

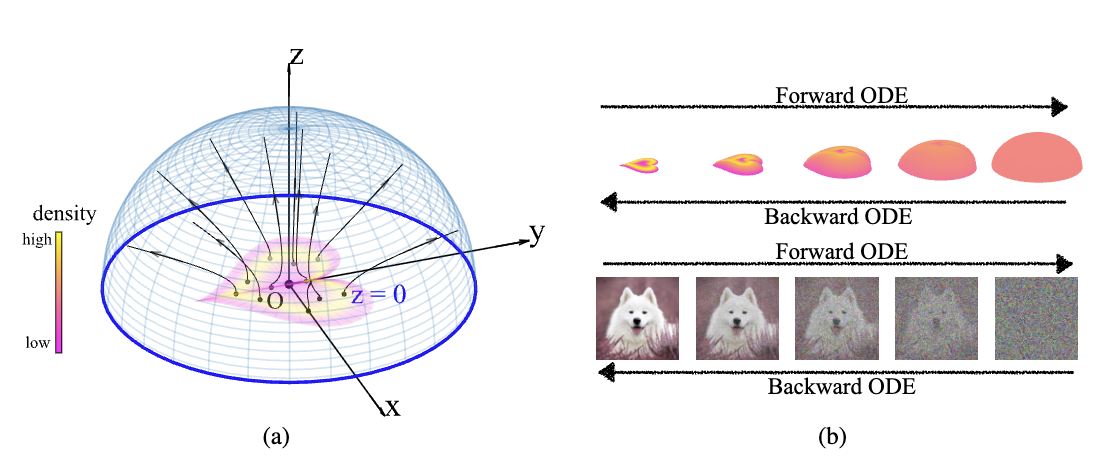

First is the Poisson Flow Generative Models, published in 2022. This work utilizes a fundamental physical phenomenon from electrostatics: the Poisson equation. In an electrostatic field, no matter how complex the distribution of charges (data points) is, the electric field lines possess the property of being non-intersecting. More importantly, if we observe from a sufficient distance, any complex finite charge distribution looks like a uniform spherical distribution. PFGM exploits this property: it treats data as charges. As long as we sample from a uniform sphere at “infinity” and flow upstream along the electric field lines, we can precisely map back to the complex original data distribution. Here, physics provides a natural geometric path to map a simple distribution (a uniform sphere) to a complex one (image data), which is the very essence of generative models.

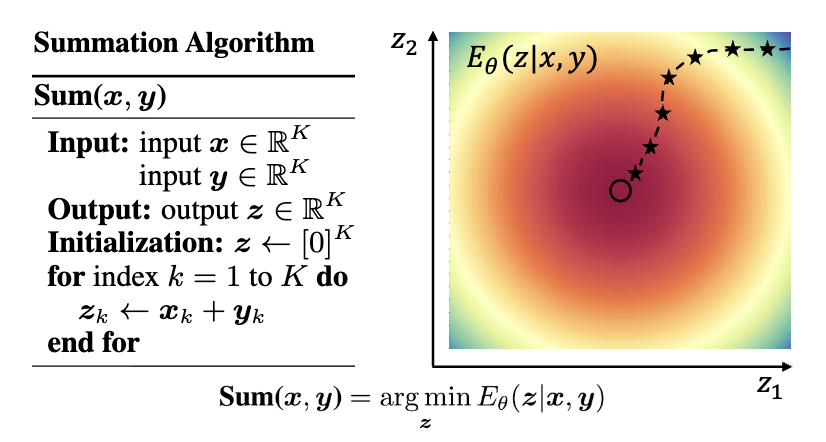

Another example is Energy-Based Models (EBM). In physics, the stable state of a system often corresponds to a minimum of “Free Energy.” Free energy consists of two parts: potential energy (the system’s energy state) and entropy (the degree of disorder), balanced under the regulation of temperature. EBM introduces this concept into AI, not only for generation but also by redefining the inference process as a process of energy minimization. This forms a mathematical isomorphism with the “Free Energy Principle” in cognitive science—the idea that biological intelligence tends to minimize surprise.

The third example comes from our own research: Diffusion Models are Evolutionary Algorithms. We observed that the denoising process of diffusion models can be mathematically decomposed into two parts: a deterministic “drift term” moving towards the data manifold, and a stochastic “noise term.” This is strikingly similar to the process of biological evolution: the deterministic drift corresponds to natural selection (screening for traits adapted to the environment), while the stochastic noise corresponds to genetic mutation. Based on this intuition, we proved that diffusion models are mathematically equivalent to a form of evolutionary algorithm. This transformation not only allowed us to see mechanisms akin to “reproductive isolation” within the formulas but also provided an evolutionary perspective that does not require backpropagation training.

Why are these scientific intuitions so effective? The distinction made by philosopher of science Hans Reichenbach might explain this process. He divided scientific activity into the “Context of Discovery” and the “Context of Justification.” The former refers to the psychological process by which scientists acquire new knowledge—often filled with intuition, conjecture, and even irrational inspiration; the latter is the process of rigorously proving and formalizing these discoveries using logic and mathematics. Science for AI utilizes mature structures from other scientific fields as the “Context of Discovery” to gain intuitions about intelligence, which are then substantiated within the “Context of Justification” through AI engineering practices.

This is the power of analogy. As cognitive scientist Douglas Hofstadter argues in Surfaces and Essences, analogy is not merely a rhetorical device, but the “Fuel and Fire” of human cognition. We map structures that operate well in physical or biological systems (the source domain) onto algorithm design in artificial intelligence (the target domain). This is not simple imitation, but rather a hypothesis that different scientific fields may share the same underlying mathematical structure—much like the shadows in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, physics and AI may simply be shadows cast by the same “mathematical entity” from different angles.

From this perspective, Science for AI is a response to and a revision of Rich Sutton’s famous essay, "The Bitter Lesson."

In his essay, Sutton reviews seventy years of AI history, proposing a discouraging but powerful point: leveraging computation for search and learning is always more effective than leveraging human knowledge. He argues that researchers tend to design AI based on their own understanding of thinking (e.g., Go joseki, linguistic grammar rules), a practice that is effective in the short term but is invariably surpassed in the long run by systems that simply utilize massive computation and general methods. This is because human introspection is often biased and difficult to scale.

Sutton’s point is correct when it involves “human experience,” but I believe he overlooks another source of knowledge.

Science for AI introduces not subjective “human experience,” but objective “scientific structure.” Physical laws and evolutionary mechanisms are not subjective human inventions, but cosmic mechanisms verified over eons. Introducing such structures into AI is fundamentally different from manually coding Go rules. We are not teaching AI how to play chess; we are endowing it with a “brain structure” that conforms to natural laws.

This type of analogy can be divided into three levels:

- Phenomenological Level: Imitating appearances. For example, seeing a bird fly and attempting to build an ornithopter. This often stops at the surface and fails to touch the essence of intelligence.

- Mechanism Level: This is what I consider the most critical entry point for Science for AI. At this level, we focus on evolutionary algorithms, statistical physics, field theory, etc. They are neither as superficial as the phenomenological level nor as abstract as first principles. They possess rigorous mathematical structures and excellent properties, explaining why a system has adaptability, while simultaneously remaining computable and practical. This is the best bridge connecting scientific intuition with engineering implementation.

- First Principles Level: Pursuing the most fundamental explanations. For example, Solomonoff Induction based on Kolmogorov complexity. While this theoretically explains general intelligence, it is extremely difficult to engineer directly due to uncomputable terms and infinite search spaces.

For Science for AI, I believe the Mechanism Level is the most important and fertile tier.

In science, “beauty” often implies high degrees of “compression” and “unity.” Maxwell’s equations are beautiful because they compress all electromagnetic phenomena into four formulas; the Grand Unified Theory in physics is fascinating because it attempts to explain everything with a single structure.

AI for Science is a pragmatic exploration, whereas Science for AI carries an aesthetic necessity. The emergence of intelligence should not be a chaotic heap of engineering, but should follow some concise, universal mathematical structure. In this sense, Science for AI is not only about building stronger AI but also about rediscovering, within the construction of artificial intelligence, that isomorphic beauty of intelligence which pervades the physical and biological worlds.